Why this is interesting: cross-disciplinary conversations about how we move ourselves and our stuff from A to B are rare. This conference proved that they’re vital.

Mobility | Society was unlike any mobility conference I’ve ever been to, and it’s the mobility conference I wish we’d been having all along.

It wasn’t about modes, emissions, and business models.

It was about what drives our need for mobility in the first place: connection, freedom, and resources.

And it was about the costs of meeting these needs that we rarely consider.

The Nederlands Dans Theater opened, exploring how, in our ego-driven self-obsession, we are disconnected from our true nature, from one another, and from our planet. Through movement and music, the dancers posed the age-old question: if you can’t love yourself, then how the hell you gonna love somebody else?

Or: if we are disconnected from the people and planet around us, how can we hope to design a system to share what belongs to all of us?

Carolyn Steel, an architect and researcher on the relationship between food and cities, took a step back to describe one of the ways in which this disconnection came about.

Even as we moved in to cities, she said, we remained connected to the land around us. The markets and the food routes that supplied them made it clear that natural resources were flowing in from the hinterlands for our collective benefit. In London, for example, it was hard to ignore the presence of the Smithfield, Billingsgate, and Covent Garden markets as they provided meat, fish and vegetables.

But, ever the innovators, the Romans gave us an early hint of the disconnection from land and food that was to come. With over a million citizens to feed, the city of Rome imported produce from across the empire, and Romans became the first to be distanced from the sources of their nourishment. In so doing, they invented the concept of food miles.

But it was with the advent of railways and monocultural farming — think of the grain and meat farms of the American mid-west — that food and the land from which it comes became abstract concepts in the modern era.

We no longer connected with the farm or the farmer.

We couldn’t imagine the immense abattoirs in Chicago.

Nor need we notice the first refrigerated railway cars as they slid in to our cities, loaded with industrially-produced meat.

We began to buy food cleaved of any connection to land, or any sense of the true cost of its production, a behaviour reinforced and expanded by the arrival of the supermarket. In wealthy countries, all we now know is abundance, and nothing of the true cost of its production.

Steel acknowledged that, as Aristotle’s political animals, we are bound to thrive in cities. As a species, we need social connection to cohere and to create. And, as Horace Dedieu has pointed out, for this reason it’s from cities that the future will spring.

But Steel wondered whether the pendulum has swung too far, and whether our increasing isolation from the land and lack of visceral understanding of how it provides for us will make it difficult to fight for its restoration and preservation.

Suggesting a way forward, Steel closed with a reflection on Utopian architecture and urban planning.

Utopia has its roots in the Ancient Greek for either *eu* (good) + *topos* (place), or *ou* (no) + *topos* (place), the latter interpretation suggesting a perfect figment of the imagination, rather than any attainable reality. She proposed as an alternative the idea of a *sitopia*, a place designed around and celebrating sitos, our source of nourishment: food.

The Garden City Movement, she suggested, is the closest we’ve come to striking an ideal connection between industry, agriculture, and living. She went on to suggest that the emergent decoupling of knowledge work from city centres provides us with a perfect opportunity to imagine how we might plan cities anew, and replan the ones that we have.

Storyteller and poet Kader Abdollah ran with the theme of imagination. If we can imagine something, then it is real. Imagination, he said, begets an idea that we can rally ourselves to realise.

It was a beautiful segway in to a presentation by economist Mariana Mazzucato which addressed the way governments have moved from a position of investors of first resort, to lenders of last resort.

Governments, she said, used to engage in outcome-oriented investment. Great leaders imagined something, then rallied government resources to achieve it.

This approach underpinned the American moon programme, the creation of the internet, and the development of nuclear weapons and energy, creating markets for associated products and services in the process.

Key to achieving these outcomes was building strong intergovernmental relationships that oriented institutions towards the same goal. Frameworks for public-private partnerships recognised the profit motive, but were designed to kept profit-seeking in check. And contributing organisations were cross-collaborative, co-creative and self-sustaining when it came to nurturing talent. A dependence on consultants and their “brochuremanship”, leaders realised, wouldn’t move the needle on getting to the moon.

All this stands in stark contrast to the role that many governments play today, which is to clean up after private sector profit seeking goes wrong. The late-to-the-party responses to ride sharing, shared micromobility, and instant delivery are perfect examples of this failure.

Today, the corporations to which innovation has been devolved invest if they can accrue shareholder returns. This means that they only invest in safe bets. Under this financialised model, she said, getting to the moon — with its enormous cost and manifold failed experiments — would, today, be impossible.

And yet the challenge we face in averting a climate catastrophe is just such a moon shot. If our governments can’t collectively orient our vast resources towards solving it then we are doomed to fail.

Annelien de Dijn, a professor of modern political history, admitted that, at first, she was confused as to why she was invited to talk at a conference about mobility. But her research on freedom provided a framework for understanding how personal mobility has gone wrong in the 21st century, and how we might start to change course.

In John Stuart Mills’ liberal conception of freedom, we should be free to live as we wish, as long as we don’t cause harm to others.

This framing has predominated in the post-war era, and de Dijn presented it as a fear-based response to the the threat of communism, which curtailed individual freedoms to devastating effect.

But it’s this liberal ideal, and the associated belief in individualism and self-determination, that has given rise to the idea that we are answerable only to ourselves and our own goals. De Dijn said that this has led to a “dictatorship of self-interest”.

It’s through this lens that we start to see how the car can at once be lauded as an enabler of an individual’s freedom, even as it deprives others of their own.

De Dijn presented another conception of freedom, however, one which is more conducive to solving both the challenges we face in providing equity in mobility, and in solving the climate crisis.

With its roots in the work of Dutch philosopher Spinoza, and popularised by Rousseau among others, the philosophy of the social contract describes a freedom that is collectively determined and, therefore, democratic in its nature.

Crucially, and paradoxically, it is a freedom defined by constraints.

By surrendering the ability to drive however we like, for example, De Dijn showed that we experience greater liberty. The constraints of traffic laws ensure that traffic can flow. This allows us to reach our destination in a reasonable time, and reduces the risk of us having an accident that might inconvenience or incapacitate us.

De Dijn then went one step further, taking issue with a point made by Renault design chief Laurens van den Acker.

During his pre-recorded presentation, he spoke of the car as one of the ultimate tools of personal freedom.

De Dijn acknowledged that the idea that a car enables freedom is plausible, in as much as it enables the driver to get from A to B and achieve their goals. But she argued that this is a classic liberal conception of freedom.

When we consider that the use of a car for personal mobility - with its outsize consumption of space, energy and other resources - denies others equal opportunity to achieve their goals, it’s no longer the freedom machine van den Acker claims it to be.

And when we factor in the externalities that enable the car to exist — the pollution, land and social degradation, and health impacts that the driver doesn’t have to pay for — it’s hard to ignore how freedom-taking a car really is.

And it was this idea, of robbing Peter to pay Paul, that sat at the core of Reuben Terlou’s presentation.

A physician, photographer and documentary maker, he’d not long returned from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

There, he witnessed the devastation caused by the ongoing civil war. And he saw how cobalt — key to the production of many devices we consider essential — plays a central role in the unimaginable violence.

He shared a photo of a woman he interviewed.

She had been raped five times by the militia controlling the mines.

Her daughter, born of that rape, was raped.

And her grand daughter was raped, too.

These are costs, he said, that we don’t consider when we buy that new iPhone, or that new Tesla.

But these costs are being paid, by people that we can not see. And they’re paying a price that we ourselves would not tolerate.

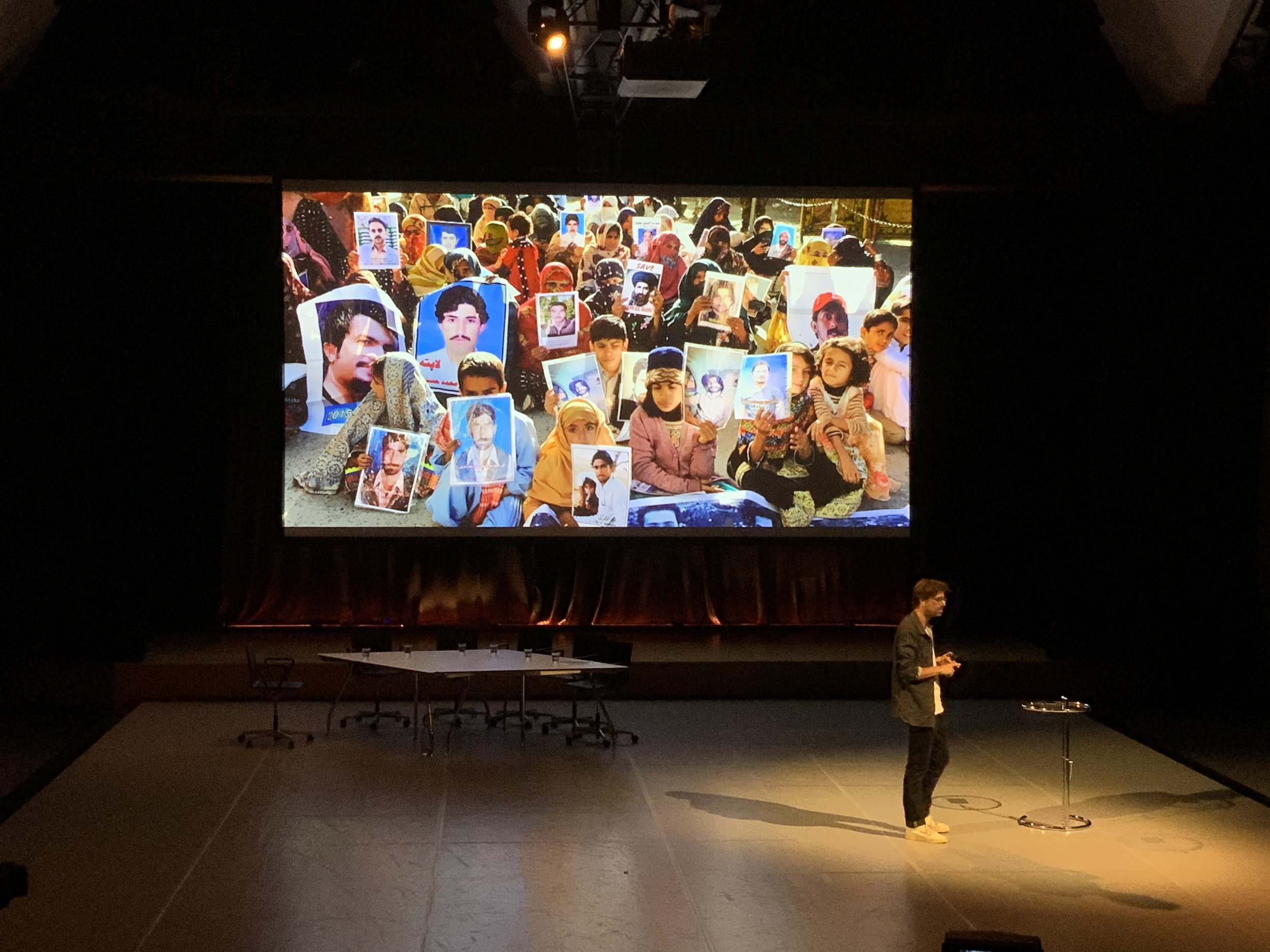

Take the residents of Gwadar, Pakistan, for example, who are paying with their livelihoods and lives for China’s access to the Persian Gulf. From here, China gets 60% of its oil. And from here, China gets the energy to manufacture goods for the rest of us.

Herein lies the greatest lesson of Mobility | Society: everything is connected.

We are connected to each other.

We are connected to our natural environment.

And we ignore this connection at our peril.

The conference was a powerful argument for moving beyond self-centred human-centred design, and suggested an alternative.

To meet the global challenges that we can no longer ignore, we need a design that is systemic in its purview, a design that respects the environment that sustains us all. And we need a design that respects the needs of everyone, not only the wealthy. In her closing remarks, moderator Nanjala Nyabola called on us all to consider the people that most need freedom of mobility - refugees and the displaced - are the ones who are least likely to receive our attention as designers.

As I live tweeted Mobility | Society, I received messages from friends who work in the automotive industry.

They wanted to be there. They wanted their colleagues and bosses and boards to be there.

They recognise the conference gave voice to conversations they and their organisations need to be having, but of which they are either ignorant, or ignoring.

That Laurens van den Acker and Adrian van Hooydonk, design chiefs of Renault and BMW Group respectively — people and organisations that are responsible for the future direction of the automotive industry — meant the other panelists spoke on their behalf, depriving them of a voice in a critical debate, and leaving them and their employers open to reasonable but unanswered criticism.

Another industry friend asked me how we might take these conversations to car companies.

At first, I took inspiration from Upton Sinclair, who quipped “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it”.

But the fact that industry people wanted to be there, that the ideas shared excited and interested them, and that the implications of our current trajectory shocked them, gives me hope that the beginnings of the conversations are already there, within these folk.

We now need to create the space to let the conversations and connections unfold.

Mobility | Society was hosted by TU Delft. Click here to find out more about the Mobility | Society movement, and to stay up to date with their events.