Why this is interesting: as car makers try to increase margin through subscription services, social networks offer some clues as to how they might succeed.

Mercedes recently announced a subscription performance upgrade to its high-end EQ series of electric vehicles.

For $100 a month, or $1200 a year, you can increase the performance of your EQE, EQS, or EQS SUV by 0.8 to 1.0 second over the 0–60 Km/h sprint.

Mercedes clearly hopes that it can gain recurring revenue from its customers with this subscription, increasing the margin it can extract from its customers. I’m not so sure it’ll pan out like they hope. Here’s why.

Status as a Service in social networks

In 2019, Eugene Wei wrote an article called Status as a Service (StaaS). In it, he argues that for a social network to succeed, it needs to fulfil one of two human needs. Ideally, it will fulfil both.

The first need we have is for utility. Think of WhatsApp and the way it connects us to people anywhere for nothing more than the cost of our cellphone plan.

The our second need is to signal our social status to our peers because, as Wei says:

People are status-seeking monkeys.

And:

People seek out the most efficient path to maximizing social capital.

TikTok, and what Instagram has become, are great examples here. They’ve turned accruing status among our peers in to an easily-accessible game, while being low on absolute utility.

The holy grail, of course, is to offer both utility and social capital. This is a combination with which WeChat – with its mix of retail, payment, and social media features – has had phenomenal success in China.

As automakers like Mercedes turn to subscription services to increase margin, I think Wei’s framework offers an interesting way to assess whether these efforts will succeed.

Cars, utility, and status

A Dacia Sandero. Low status compared to a Mercedes-Benz, but high utility. Image: Dacia

So how do cars stack up overall when we assess them on utility and status?

To assess their utility, we might ask: does the car allow me to fulfil all the basic demands I might have from it? Does it get me from A to B reliably? Does it offer me adequate protection in an accident? Does it have sufficient space to store all my stuff?

As my mate Joe Simpson pointed out in episode 3 of Looking Out - The Podcast, all modern cars, in fact, fulfil the need for utility to a greater or lesser extent. Whether it’s a €15,000 Dacia Sandero or €109,000 Mercedes EQS, every car on the market fulfils the basic requirements for performance, safety, reliability, comfort, efficiency etc. There’s now little easy competitive advantage to be gained in trying to greatly improve utility.

To assess the efficiency with which a car helps me accrue social capital, we might ask: does the car signal to others that I am a high-status individual, particularly relative to my peers with whom I’m playing the status game?

The signalling to others is the critical component here. Others need to see and recognise that our car is better than theirs. This is how we become reassured that we sit higher in the social hierarchy.

I’d argue that this is why we have seen a wild proliferation of cars built off the same underlying mechanical architectures. Manufacturers are devising new status games within existing model hierarchies, giving customers more opportunities to play against their peers within a particular price range. Through this lens, some of the most bizarre products of the past decades, like the coupe, cabriolet, and high-performance versions of SUVs, start to make perfect sense.

Mercedes and status games

A Mercedes-Benz S63 AMG E Performance oozing status. Image: Mercedes-Benz

Historically, Mercedes has effectively positioned their products to facilitate status games.

They have a clear model range structure – A, B, C, E, S and so on. This makes it easy to identify which model is bigger/better than the preceding one.

Historically, they’ve also had a logical numbering scheme for model variants – think 280, 400, 500 and (my favourite, because I too am a status-seeking monkey) 600. So far, so easy when identifying the superior car within a model range.

With the arrival of mass-market AMG cars, a new performance level was added on to the top of mainstream variants. This was marked out by a new badging scheme – A 45 AMG, E 63 AMG, G 55 AMG, S 65 AMG. The cars were also differentiated with the addition of (outrageously) upgraded powertrains, distinct bodywork and trim, bigger wheels and tyres and louder exhausts.

More recently, starting in around 2010, Mercedes made the smart decision to reflect some of that AMG glory back on their more humdrum cars. With the introduction of the AMG-Line, you could give your lowly A 180 or C 200 a bit of glitz and glamour. This arrived with the fitment of larger wheels that aped the full-blown AMG designs, a different grill, and some different trim outside and in.

And Mercedes has also played the proliferation game, offering all manner of status-accruing variants on common architectures, like their SUV and 4-door coupe models.

All of this is to say that Mercedes really knew how to to help owners signal their status to others.

The failure mode of the $1200 performance upgrade

Let’s return now to the performance upgrade for the Mercedes EQ EVs with which I opened.

Their basic utility of the underlying cars is, as we’ve established, unquestionable. They have sufficient space, comfort, safety and performance (none of them is slower than 6 seconds from 0 to 62 mp/h). The subtraction of another second from the sprint is going to make little-to-no appreciable difference in accomplishing everyday tasks, so won’t increase the vehicle’s utility.

That means that Mercedes must be banking on the social capital effect of the $1200/1.0 second upgrade to sell it and keep people paying the subscription.

And here’s where the idea, in my opinion, falls apart: there’s no way to tell by looking at the car that the upgrade is fitted. There’s no badge, no bigger wheels, no new bodywork. And – because EV – there’s no popping, crackling exhaust. There’s nothing to make it obvious you’re forking out money on a recurring basis to have a marginally quicker car. Therefore, the owner’s higher social capital is not legible to their peers in an obvious, meaningful way.

And to add insult to injury, it’s not as if your upgrade allows you to point to a better motor, as you might with a traditional AMG model. This is because you’re simply paying to uncripple the motors that were fitted to the car at the factory.

So with no increase in utility, and no increase in social capital, why the hell would you pay for it?

Automotive upgrades that satisfy Wei’s theory

Let’s contrast Mercedes’ approach with two other examples.

Firstly, BMW.

In some markets, BMW now charges a subscription for heated seats. Like the Mercedes EQ cars, the hardware required for the upgrade is fitted at the factory, so you’re simply paying to unlock the software that sends electricity to the heating elements already in the seat.

Put aside for a second, if you can, arguments about the waste of fitting vehicles with hardware that owners can’t access, and instead focus on the utility/social capital matrix.

If you live in a cold climate or have back pain that benefits from a little warmth, then the addition of heated seats offers a marked improvement in utility. And if you carry a passenger, then that increase in utility is accompanied by an increase in social capital. By facilitating the comfort of your companion with this extra feature, you also demonstrate your higher social status.

By Wei’s theory, then, the BMW upgrade should find success in the market, once people get used to the idea of in-car subscriptions.

Secondly, let’s turn to Polestar which, like Mercedes, offers a performance upgrade for their Polestar 2 EV.

Some of the signifiers of Polestar’s Performance Upgrade for the Polestar 2.

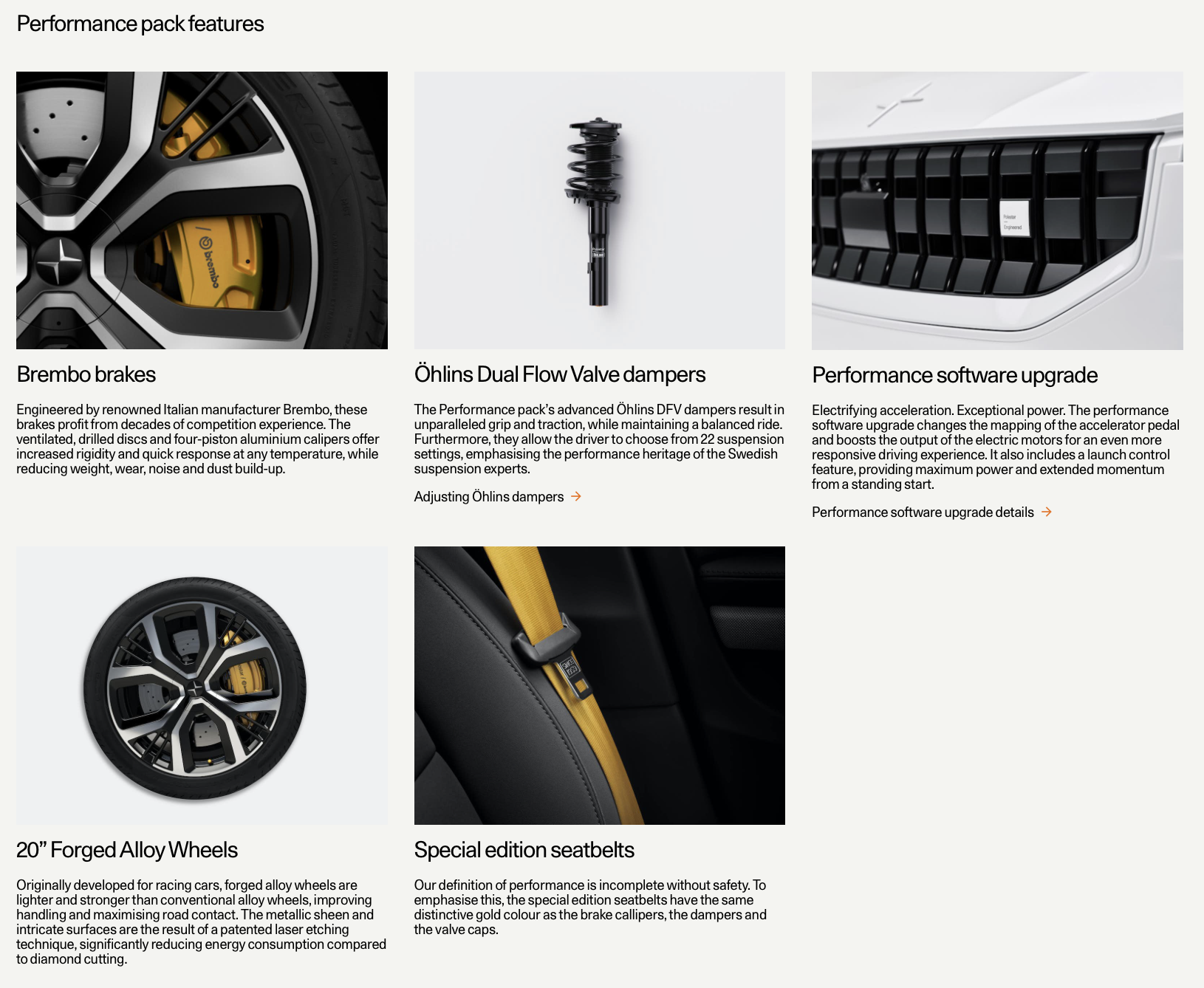

Like Mercedes, Polestar is uncrippling the motors fitted to the car at the factory. Blurgh. But unlike Mercedes, Polestar charges a one-off fee of €6,500 and – here’s the kicker – fits a whole bunch of status-signalling parts as part of the deal . These include 20’ wheels, adjustable Ohlins shock absorbers, Brembo-branded brakes with a distinctive gold finish, seatbelts finished in the same colour, and distinctive stickers. Polestar even calls out the social capital-raising qualities of these stickers in their sales material:

Tell the world about your power boost. When ordering the performance software upgrade as an aftermarket download, you will also receive new door stickers with updated power information, plus a rank mark sticker for the car’s front grid. Mounting instructions are included.

Polestar’s upgrade is also available over-the-air, after the car has left the factory. In this case, you won’t receive the upgraded components. However, Polestar will go to the trouble of sending you your status-signalling stickers by post, along with instructions on how to fit them. See how important those stickers are?

And if you’re worried that you still might not impress the superiority of your upgraded PS2 on your passengers, Polestar offers the following reassurance on their website:

Is there a way to see how the performance software upgrade improves the acceleration time?

Yes, there is. We’ve developed a dedicated in-car Performance app that can be accessed from the centre display. It provides acceleration figures as well as the number of G’s that the car pulls. The Performance app can be downloaded for free from the Google Play store.

The only way Polestar could improve on the signalling of your status is if they offered up a digital leader board, a place that showed which of their owners were the most hardcore in their use of their increased performance. It would be a neat bit of signal amplification and I’m only sorta joking here.

Conclusion

So Polestar and BMW get it. They understand that in order to get people to pay for an upgrade, it either has to meaningfully increase the utility of the vehicle, or increase its ability to signal the social capital of its owner to others. Or, ideally, do both. Sadly, the Mercedes performance upgrade does neither of these things.

I have a sense that these sorts subscriptions are here to stay. The economics of producing cars are increasingly difficult, and unlocking already-built hardware with a subscription is too-tempting a proposition for OEMs to ignore.

But if car makers are going to go down this path, then they need to do it right to succeed, and pander to our basest instincts. We're status-seeking monkeys after all.